I have looked into this topic before in Part 4 The nude- What it means to be naked. Looking in detail at the male gaze and what that means for the female subject of the painting. For my Personal Project I want to look at the other side of the fence in more detail and what it means to look at a person, male or female, within a female gaze. I will be looking at the female body to start with and then will advance onto a male body. I want to look into female empowerment along the way, and what it means to be an empowered woman, and a good place to start with female empowerment is looking with a female perspective.

The Male Gaze and Male Artists

I will keep this part brief as a lot of this topic I have already covered in the linked blog post, but as John Berger says, ‘Men act and women appear‘ (Berger, J. (1972))It is extremely common in historical pieces that women are presented in an objectifying way. They are not people, but prizes to be earned by men, to be looked at for pleasure. Men depict naked women in their work because they like to look at naked women, and then shame the woman in the painting for being such a way. Women are objectified in so many pieces, and then blamed for it when it is the vision and creation of a male painter. As looked at in my linked blog, many men place the blame on women by painting them looking into a mirror, shaming them for supposed vanity.

However, one of my personal favourite artists, Edward Hopper, has a more unique way of painting and portraying women which I have always been drawn to. He is a magnificent painter, who creates scenes, a lot of his work feels like you’ve stepped into the middle of a movie and are left to figure out what is happening.

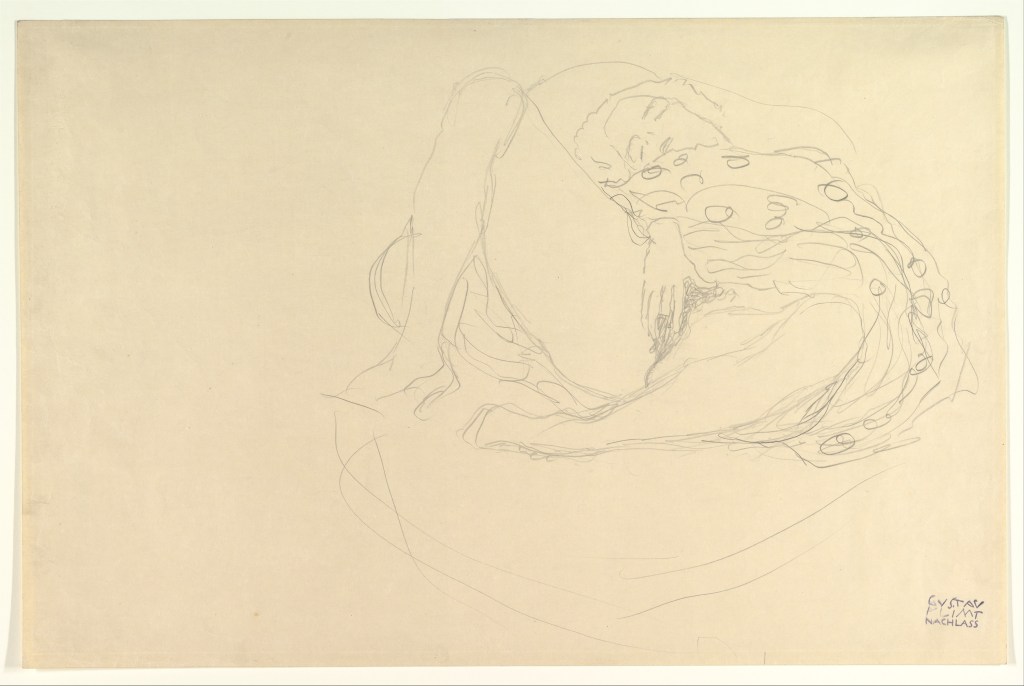

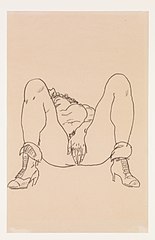

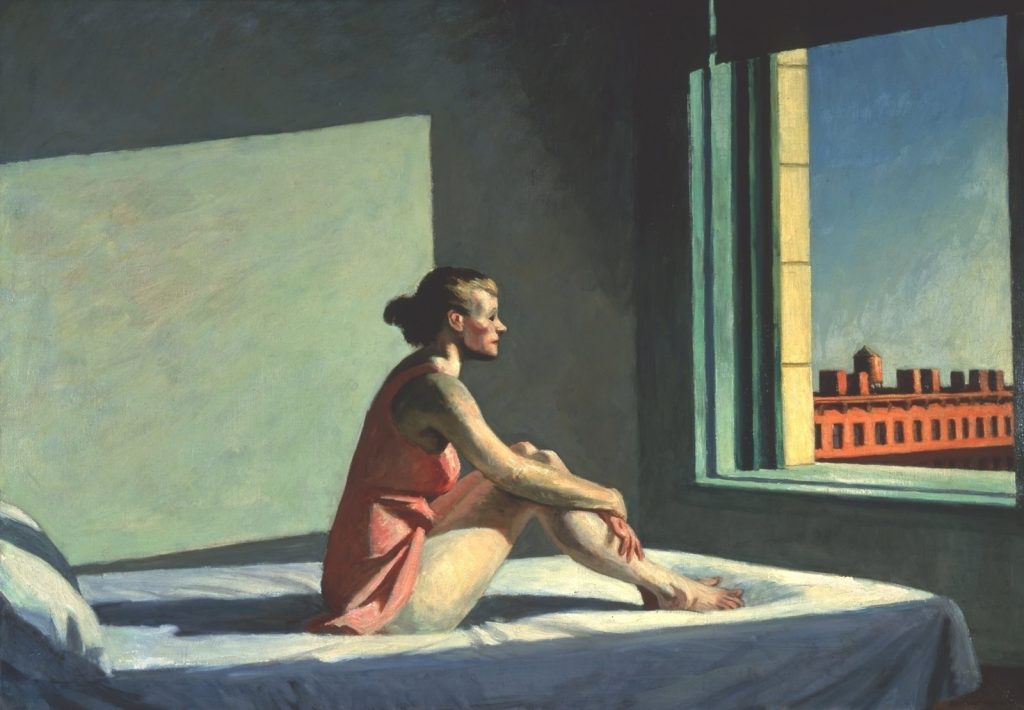

This piece here sits within the female gaze. The woman portrayed is not objectified or sexualised, she is depicted in a relaxed state, just enjoying a peaceful morning to herself. This romanticised and empathetic point of view, which fits very well into the female gaze, is most likely due to him often modelling the women in his paintings after his wife, Jo. So that feminine lens of care and love that fits into the female gaze is from a place of real affection. And its such a wonderful take from a male painter from this era, where men like Schiele, Klimt and Picasso were beginning to explore the female form in a more sexual manner, using their art as a way of expressing their fantasies with the female form. We can see to these two pieces by Klimt and Schiele to the left that they overly sexualised women in their drawings, and I find it uncomfortable due to the context that these drawings come from male artists who get pleasure from depicting women in such eroticised ways. The women aren’t seen as people here but their sexual organs, vagina and boobs. They don’t have feelings or their own desires, they exist in these drawings just to please the male viewer.

In-text citation: (Hopper, 1928)

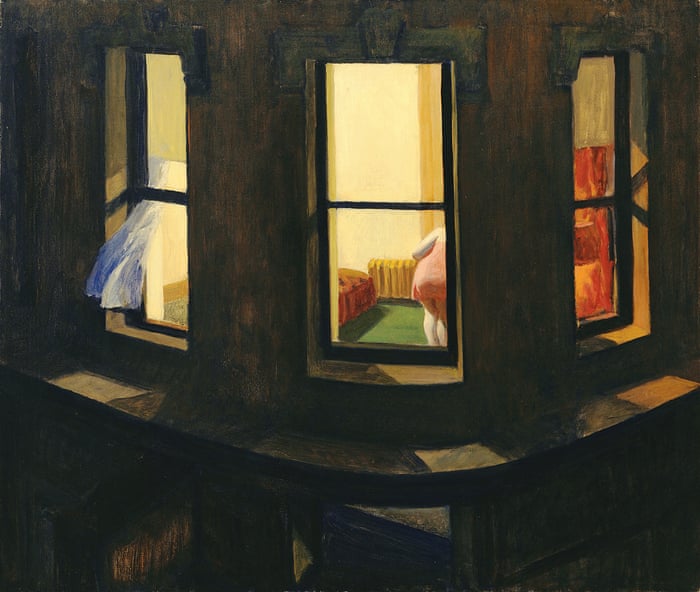

However, with this piece ‘Night Windows’ by Hopper we can see a more objectifying portrayal of women. The piece is stunning with Hopper’s approach to light and tone, with the bright yellow colours luminating the dark surfaces of the building outside. However with the context of this being a male painter, while this does portray a woman just living and not necessarily objectified for male pleasure, we are still looking from a predatory perspective from outside the window. And predatory behaviour can appeal to men in a sexual and inappropriate way. We do not have the woman’s consent to be looking into her room while she changes. This painting takes a creepy and predatory look at an unsuspecting woman, it feels wrong to watch her as she is unaware. This definitely fits into the male gaze, not the female gaze. This painting could also fit into the male fantasy of stalking and harassing women.

We can see here with Hoppers earlier work, even with his later approach to romanticising the women in his paintings, he still fell into the a common practice for male artists to objectify women. It’s great to see how much his work has progressed to fit more into a female gaze. His later approaches are a refreshing take on the portrayal of women and fits very well into the current climate of Lockdowns and social distancing with people alone in rooms and scarce streets.

Hoppers approach to women living and and being themselves in their own space is something I’d like to carry into my own work. I’d like to do similar portraits to his paintings like ‘Morning Sun’ and look at romanticising the person in the piece rather than objectifying. Empathy is a key characteristic of the female gaze, which I will look into shortly, and I want to create a sense of that between the subjects of my drawings and the viewer. I want to create a connection and relation rather than objectification. And Hopper clearly does that well in his later, less objectifying pieces.

The Female Gaze

The Female Gaze does not have a Google definition unlike the Male Gaze, which is quite interesting. it is much more open to be widely defined by female Artists. Although some of Hoppers work fits into a female gaze, some of his work still heavily holds onto a male gaze (some points of view making him look more like a peeping tom on women), he is still clearly views some women in his work as sexual objects to be viewed rather than people. A lot of what the Female Gaze can be boiled down to is female frustration of the Male Gaze, how it exists beyond women being depicted in art and how it takes control of our life. Florence Given talks about this well in her book, how the Male Gaze deeply affects women, it festers inside of us as internalised misogyny, it makes us so we can’t live our life normally. When we’re outside we are always aware of our surroundings and concerned for our safety. She explains how our bodily autonomy is questioned due to the perception of men; ‘I have a very confusing relationship with my body; there are times when I feel as though it doesn’t belong to me. Equally there are times when I genuinely do not feel safe in my own body’ .’Maybe it’s because the perceptions I have about it are based on hetero male gaze standards and not my own’ (Given,F.(2020)) . This is practically a universal experience for all women. And Art History with the strong Male Gaze has heavily influenced our view on women.

‘What kind of a relationship are we expected to have with our own bodies, if not a conflictual one, when we are socialised to believe that they exist for male consumption?’ .

The Female Gaze is intended to turn the Male Gaze on its head. Women are to be viewed as people, not objects or as Berger says ‘to appear’ , we are more than a pleasing image. A lot of female artists tackle this subject matter by graphically displaying the female form in a natural or even grotesque way, rather than something perhaps conventionally beautiful, easy for a male viewer to consume and sexualise/objectify the women depicted. Katya Lopatko describes the idea of the Female Gaze well in her website article; ‘The opposite of the male gaze is what we call the female gaze: an empathetic, empowering gaze that emphasizes the subject’s agency and rich internal landscape.‘ . The Female Gaze is an interesting approach, filled with empathy and understanding for the people depicted, mostly women. It is about regaining that control over a female image from men, and often looks at personal experiences. Often sexual.

This work by Helen Beard is a unique approach of lively feminist art looking from a female gaze. She doesn’t shy away from the typical feminist approach of looking at nude female body, but her colour palette of bright pastels helps to reinforce that the female body is a positive thing. It is lively and fun. She takes graphic depictions of the female body and sex and blows them up painting them in bright colours, loud and proud. Her work narrows down the body to loose shapes that make it up and promotes and celebrates female body positivity as well as female pleasure. Her works empathises with the female body and experience rather than objectify, which is what the female gaze is about. Helen Beard says of the Female Gaze and Art, that “Art should seek to tell the story of a female protagonist, through female eyes and garner some parity in a continually unequal world.”. The Female Gaze is truthful and seeks to show women the vulnerabilities of being female without the shame. Without the objectification.

Samantha Louise Emery’s approach is different, she doesn’t have a strong focus for the female body, but what is beyond it. She maintains a deep focus on women’s auras which is evident from her piece ‘Laurie Anderson’ shown above. Emery says about her work that “When I look at my subject, I see another version of myself, as I do believe we are all mirrors. Woman to woman, I feel that I can relate on a much deeper level.” She looks at exploring the female form beyond the traditional Male Gaze, to look at the identity of her female muse, not just the outward appearance, but exploring the relationship between outward image and the inner character, portraying women with a strong presence rather than just to appear for men.

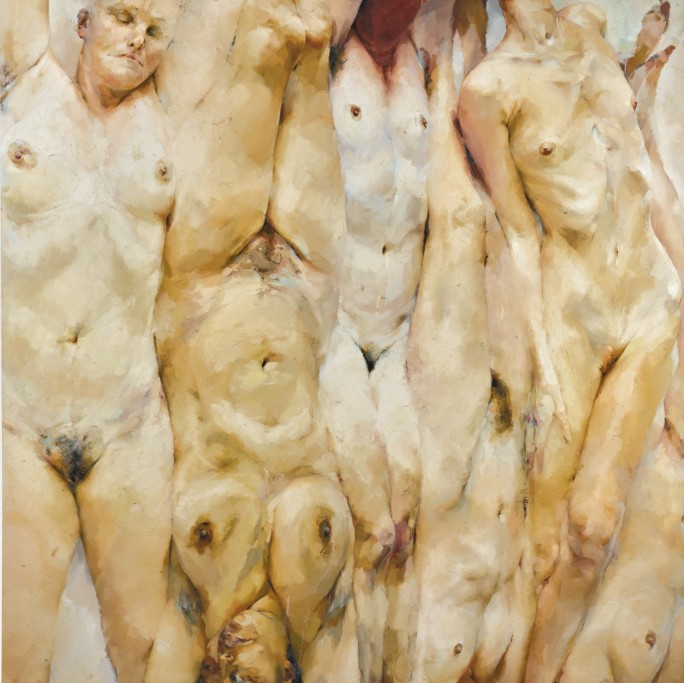

Jenny Saville, one of the most famous female painters in contemporary art, has a more grotesque and real approach to the female form. It is reality of the human body, and was groundbreaking at the time. Looking at an unappealing take on the female form. This piece, ‘Shift’, looks at dismantling the idea of what the ideal female body has been portrayed as by the Male Gaze in art and media for so long. There can’t be one ideal or idea of what the perfect female body is, when every body is different and unique and everyone’s body is imperfect, and that is setting a real standard for female nude. Bodies have curves or are skinny. Thighs are big and stomachs are never flat. Her work on the female body shatters the expectations men have for women and their bodies.

While for many women and female artists this work can be empowering, there is a problem with the Female Gaze, the depiction of a naked woman, regardless of context or meaning is open to be objectified or sexualised by a male viewer. It makes me question if I can still make work like this and be empowered if I am to be sexualised too? Its difficult as drawing my body after a lot of abuse and trauma surrounding it can feel freeing and powerful for me as a woman and as an artist, but there is still a discomfort of being sexualised against my will and the intentions of my work. You cannot control how your work is received by the viewer. For me I still feel strong creating work surrounding my naked body as I have learned over the years to not care about other people and how they view me. But it is still something a female artist should come to terms with when creating this kind of work. I think if the Artist find it empowering then it simply is regardless of how the male viewers take it. But it is open to discussion.

For my work I want to look at exploring the Female Gaze in a variety of ways and mediums, and look at using art depict my traumas with my body and experience with men. I want to create empathetic pieces of work that look at both the female and male body in a more intimate and loving way rather than being objectifying. I want to make art that is personal to me but is relatable to my viewers. I want my viewers to look at my work and empathise and relate to the people of my portraits. I will be working on a lot of self portraits and how I view my body and also looking at a male body and depicting it in a romantic way. Through a female perspective. Using friendly colours like Helen Beard could be a good way of achieving this, as it adds a friendly layer to graphic female content. Or trying to depict the essence of the person through mixed media as Emery does with her work looking at women’s aura.

To start I want to make artistic responses to personal female experiences of mine but also current events surrounding women like the Sarah Everard case.

References

Ways of Seeing: John Berger-Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. [online] London, UK: Penguin Books Limited, p.176. Available at: https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Ways_of_Seeing/QxdperNq5R8C?hl=en&gbpv=0&kptab=overview [Accessed 8 Mar. 2021].

Painting- Morning Sun– Hopper, E. (1952). Morning Sun. [Oil on canvas] Available at: https://www.wikiart.org/en/edward-hopper/morning-sun [Accessed 8 Mar. 2021].

Painting- Night Windows- Hopper, E. (1928). Night Windows. [Oil on canvas] Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79270 [Accessed 8 Mar. 2021].In-text citation: (Hopper, 1928)

Klimt Drawing- Klimt, G. (1913). Reclining Nude with Drapery. [Graphite] Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/334903 [Accessed 8 Mar. 2021].

Egon Schiele Drawing- Egon Schiele (1918). Reclining Nude with Boots. [Charcoal on paper] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reclining_Nude_with_Boots_MET_DP-1597-001.jpg [Accessed 8 Mar. 2021].

Women Don’t Owe You Pretty: Florence Given- Given, F. (2020). Women Don’t Owe You Pretty. S.L.: Cassell Illustrated.

T+heArtGorgeous (Website)- TheArtGorgeous. (2019). Three fresh takes on the female gaze. [online] Available at: https://theartgorgeous.com/three-fresh-takes-female-gaze/.

Painting- Helen Beard- Beard, H. (2019). Syntribation. [Oil on canvas] Available at: https://www.helenbeard.art/portraiture-1/2019/4/10/2019/4/10/new-beginnings [Accessed 16 Mar. 2021].

Painting- Samantha Louise Emery- Emery, S.L. (2018). Laurie Anderson. [Latex, acrylic and embroidered gold, silver and copper on canvas.] Available at: https://www.samanthalouiseemery.art/ikona-gallery [Accessed 16 Mar. 2021].

Painting- Jenny Saville- Saville, J. (1996). Shift. [Oil on canvas] Available at: https://www.wikiart.org/en/jenny-saville/shift-1997 [Accessed 16 Mar. 2021].